Pakistan is teetering on the edge of a severe water crisis, with the Meteorological Department issuing dire warnings about critical shortages in Sindh, Balochistan, and Punjab. Over the past six months, the country has experienced an extended dry spell, with rainfall levels falling well below average. This alarming trend has placed Pakistan at serious risk of drought, threatening agriculture, drinking water supplies, and overall economic stability. This scarcity is likely to worsen in the coming days owing mainly to climate change unleashed by rapid global warming, which has already altered weather patterns significantly, as well as socioeconomic factors.

The Indus River System Authority (IRSA) has warned Punjab and Sindh, the main breadbaskets of the country, to brace themselves for up to 35pc water shortages for the remaining period of the current Rabi crops, including the staple wheat harvest. Pakistan is starting its new summer cropping — Kharif — season with an acute water shortage caused by lower-than-normal snowfall in the last winter.

While environmental challenges, erratic rainfall patterns and glacial melt contribute significantly to the water crisis, the roots of the problem extend beyond nature. Pakistan's outdated water management practices, inefficient agricultural irrigation, and lack of robust governance have severely exacerbated the situation

However, IRSA is hopeful that the monsoon rains will plug the shortage in the latter part of the Kharif season. This pattern is not unfamiliar to most of us, as it repeats itself every year without exception. Only the extent of water scarcity varies from year to year, and is sometimes followed by discord among the provinces, particularly between Sindh and Punjab, over the formula used to share water.

It is also worrisome for smallholder farmers living at the tail end of the canals. The Indus River, the country’s primary water source, is already under immense pressure due to erratic rainfall, rapid glacial melt, and inefficient water management. With reservoirs at dangerously low levels, farmers in affected regions are struggling to irrigate their crops, jeopardizing food security. Additionally, urban centres are facing dwindling water supplies, with cities like Rawalpindi, Islamabad, Karachi and Lahore already experiencing water shortages.

Experts warn that if immediate measures are not taken, the crisis could escalate, leading to mass displacement and severe economic repercussions. The government must prioritize water conservation, invest in sustainable water management infrastructure, and promote policies that ensure equitable distribution of resources. Public awareness campaigns on efficient water use and rainwater harvesting could also help mitigate the crisis.

Pakistan’s water crisis is not just an environmental issue — it is a looming humanitarian and economic disaster. Without swift action, millions could face dire consequences, including food shortages, health hazards, and economic instability. The time to act is now before the crisis spirals beyond control.

A nation parched

The water situation in Pakistan has deteriorated dramatically. The IRSA has decided that only drinking water will be supplied in April, with agricultural allocations put on hold until further review in May. The situation is particularly dire in the southern parts of the country, where dry conditions have persisted for more than 200 days. Compounding the crisis, temperatures in March were recorded as two to three degree Celsius above normal, exacerbating evaporation rates and depleting already-stressed water resources.

The warning comes amid reports that the country’s two largest dams, Tarbela and Mangla, have hit the dead level. This is in line with IRSA’s forecast on October 2 that dam storage would reach dead level towards the end of the winter crop cycle.

While some regions in the north have received scattered rainfall, these have been insufficient to replenish the country's reservoirs. The statistics are alarming: rainfall from September to March was 40% below average, leaving the Mangla and Tarbela dams at their dead levels. River inflows are critically low, further straining an already overburdened system.

Though alarming, the warning is hardly a surprise since growing water shortages for the summer and winter crop seasons have become the ‘new normal’ in the last several years due to the increasing number of dry days in a year as well as the shrinking glaciers resulting from climate change. Reduced precipitation is evident from the 40 percent below-normal winter rains and snowfall between September and mid-January this year, which have created drought-like conditions across the country.

Dry conditions persist in many areas in spite of the February rains that have largely offset drought-related risks to the new wheat harvest. Dry weather on most days has meant that the winter months were reported by the Met Office to be hotter than usual.

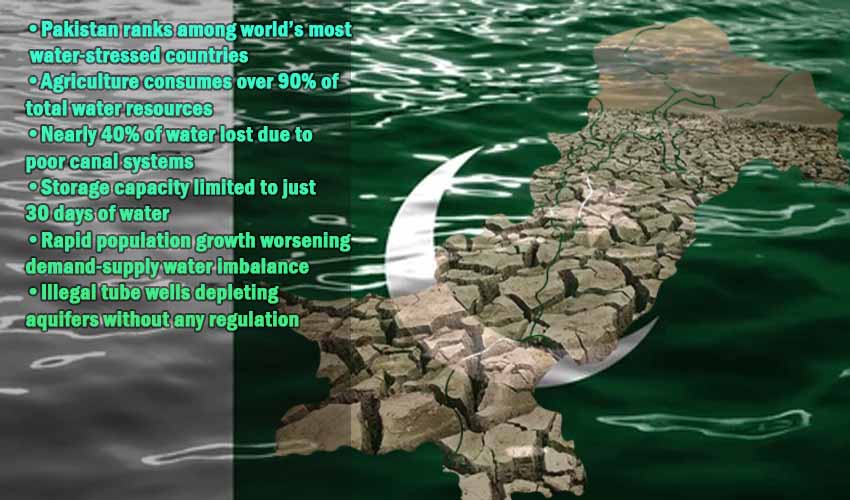

Pakistan is among the 10 countries most vulnerable to climate change, facing a worsening water crisis that threatens its future. According to the World Resources Institute’s Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas, Pakistan falls under the category of “extremely high baseline water stress.” With per capita water availability reduced to approximately 908 cubic meters, the country has already plunged below the water scarcity threshold of 1,000 cubic meters.

The increasing frequency and intensity of extreme weather events such as floods, droughts, heatwaves, and abnormal rains, show that we are already experiencing post-climate change conditions. Ranking as we do among the top 10 countries most vulnerable to the effects of climate change, we must urgently prepare ourselves for the costly and disastrous impacts of such events on our lives, livelihoods, food security and economy.

A history of mismanagement

Pakistan’s water crisis is not merely a consequence of climate change; it is equally a product of poor water management and an outdated irrigation system. Experts argue that while water scarcity is a pressing reality, systemic inefficiencies have significantly worsened its impact.

Dr. Hassan Abbas, a distinguished water expert, highlights that Pakistan’s irrigation infrastructure—designed over two centuries ago by British administration—was never meant to withstand the unpredictable climate patterns of today. “Our system is fundamentally flawed. We either suffer from severe drought due to inadequate rainfall or face catastrophic floods when there is too much. Both extremes reveal deep vulnerabilities in our water management strategies,” he explains.

Former federal minister for climate change Sherry Rehman, on the floor of the House, echoed these concerns, stressing that Pakistan’s crisis is not solely driven by declining rainfall but also by structural failures in conservation and policy enforcement. She argued that ineffective governance, lack of investment in modern irrigation technologies, and unchecked groundwater depletion have exacerbated the crisis.

Pakistan in the world's seventh most vulnerable country to climate change. While mismanagement is a critical factor, climate change remains an undeniable force behind Pakistan’s worsening water crisis

Despite being an agrarian economy heavily reliant on water, Pakistan continues to lose vast amounts due to outdated canal systems and inefficient farming practices. Experts warn that unless immediate steps are taken—such as revamping irrigation networks, implementing water conservation strategies, and enforcing stricter regulations—the country will face an acute water shortage in the coming years. Climate change may be intensifying the problem, but it is Pakistan’s mismanagement that has left it ill-equipped to deal with the challenges ahead. Addressing this crisis requires urgent reforms at both policy and grassroots levels.

The role of climate change

The Germanwatch in its climate risk report has rated Pakistan in the world's seventh most vulnerable country to climate change. While mismanagement is a critical factor, climate change remains an undeniable force behind Pakistan’s worsening water crisis. Rising global temperatures have altered rainfall patterns, leading to prolonged dry spells punctuated by intense, unpredictable monsoons.

Pakistan, despite contributing less than 1% of global greenhouse gas emissions, is among the countries most vulnerable to climate change. Erratic weather patterns, melting glaciers in the north, and increasing temperatures are all contributing to the depletion of water sources. The Indus River, the lifeline of Pakistan, is under immense strain as its flow becomes increasingly erratic due to climate-related disruptions.

While environmental challenges, including erratic rainfall patterns and glacial melt, contribute significantly to the crisis, the roots of the problem extend beyond nature. Pakistan's outdated water management practices, inefficient agricultural irrigation, and lack of robust governance have severely exacerbated the situation. Despite the looming threat, the absence of cohesive policies and proper regulatory frameworks undermines any meaningful progress. Groundwater over-extraction remains rampant, further depleting precious reserves.

Urbanization and population growth add additional strain, intensifying competition for dwindling water resources. Meanwhile, the misallocation of water for low-value crops in water-intensive regions reflects a glaring policy misstep. The consequences are dire, with agricultural productivity declining and communities facing acute water shortages.

Climate change is causing longer spells of drought, which is complicating the water scarcity problem in Pakistan. But climate change is not the sole cause of water scarcity; exponential population growth is also contributing to this crisis. For instance, at the time of Pakistan's independence in 1947, the population was low, and therefore the per capita water availability was more than 5,000 cubic meters per person per day, which made Pakistan a water-abundant country at the time. But today, it has fallen below 1,000 cubic meters per person, which is why Pakistan on the way to becoming a water-scarce country.

In future, climate change will make matters worse in a number of ways for Pakistan. First, the total quantity of water is likely to decline, thus increasing the scarcity level. Second, the water availability will become more erratic, thus increasing uncertainty and seasonal stresses and strains. Third, the increased temperatures will reduce water availability further because of higher evaporation rates while increasing crop water requirements and other water demands.

Climate change is already having a serious impact on peoples’ livelihoods in Pakistan. A major challenge is excessive heat and water scarcity and quality. The numbers are scary. By 2047, Pakistan will likely have twice the population and half the water it now has. If my math is correct, that means 75 per cent less water for each Pakistani by that time.

Every year, the water table in many parts of Sindh and Punjab is sinking by about one meter. Unless the practice of digging tube wells is regulated, this fall will continue and may speed up. In Peshawar, the water table has fallen by 30 feet in six years.

The need to meet the climate challenge is even greater when a country like Pakistan is prone to multiple disastrous events at the same time. For example, in 2022, we were first hit by a heatwave and drought and then flash floods that displaced 33m people, followed by landslides that destroyed infrastructure in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and other northern regions. Tens of thousands of those affected are yet to be resettled and re-employed.

Sadly, our policymakers are not investing enough in helping the people and economy withstand the effects of climate change, though the danger is very visible. Climate disasters can severely stretch a country’s resources. They can ruin countries unprepared for them. This year we may have averted any significant damage to our staple food despite water shortages and drought. But who can guarantee that we will be as lucky next year?

Agriculture: a double-edged sword

Agriculture accounts for approximately 92% of Pakistan's water consumption. Yet, despite the vast quantities of water used, the sector remains inefficient, with low productivity compared to global standards. Experts argue that Pakistan must rethink its approach to agriculture if it hopes to address the water crisis effectively.

Climate change is already stressing Pakistan's agricultural yields – especially for staple crops like wheat, rice and maize, which are highly sensitive to temperature and rainfall changes. Four out of every ten Pakistani households rely on agriculture for their living. Their food security is already suffering. Women and children are the first to be affected. Almost one fifth of children under five suffer from acute malnutrition, according to the UN.

Mahmood Nawaz Shah, an expert in agricultural and water affairs, highlights a critical flaw in current policies: "We continue to expand irrigation into new lands while failing to improve efficiency on existing farmlands. The cultivation of water-intensive crops like rice and sugarcane must be reconsidered."

With groundwater reserves being rapidly depleted, and the irrigation system plagued by leakage and wastage, Pakistan must shift toward more sustainable farming practices. Precision agriculture, drip irrigation, and the adoption of drought-resistant crops are essential steps toward ensuring food security without overburdening the water supply.

Pakistan needs to provide incentives to farmers to grow crops that require less water and provide more nutrition such as lentils, chickpeas, mung beans is important. These crops are rich in protein and replenish the soil. Partnerships with agricultural universities be forged to develop hybrid seeds, plants and fruit trees that can survive the rising heat and saline soil.

The illusion of dams as a solution

The debate over dam construction in Pakistan underscores a deeper crisis in water management. While proponents emphasize the need for additional reservoirs to regulate water supply, experts like Dr Hassan Abbas caution against an overreliance on large-scale infrastructure projects. Instead, they argue for a more sustainable, systemic approach.

Pakistan’s water challenges are not merely a matter of storage capacity but of inefficiency, waste, and mismanagement. A significant portion of the country’s water is lost due to outdated irrigation methods, leaky canal networks, and unchecked groundwater depletion. Rather than pouring billions into new dams, a more prudent strategy would involve modernizing irrigation systems, repairing existing infrastructure, and incentivizing water conservation at both the industrial and household levels.

Furthermore, the unchecked extraction of groundwater poses an equally grave threat. In urban centers like Lahore and Karachi, aquifers are being depleted at alarming rates, with little effort made toward replenishment. Implementing managed aquifer recharge, rainwater harvesting, and stricter groundwater regulations could help mitigate this crisis.

Climate change further complicates the issue. Erratic monsoon patterns and glacial melt make Pakistan’s water supply increasingly unpredictable. Dams, which require stable inflows to remain effective, may not provide the long-term security they promise.

Addressing Pakistan’s water crisis demands a paradigm shift—from reliance on concrete megaprojects to smarter, nature-based solutions. Without such a shift, Pakistan risks deepening its water insecurity, regardless of how many new dams it builds.

The road ahead

Pakistan’s water crisis is a structural challenge that demands urgent and multifaceted interventions. Policymakers must acknowledge the severity of the situation and implement both immediate and long-term strategies to safeguard the nation’s water security.

Experts say that a lack of water accountability and budgeting information is a significant barrier to the effective use of water resources in Pakistan. They say that water scarcity poses a major challenge in Punjab, jeopardizing agricultural production, food security and the livelihoods of rural communities.

In Pakistan, ongoing challenges in water management include the absence of reliable annual water accounts, essential for detailing water availability — covering surface water, groundwater and rainfall—as well as their various uses in domestic, industrial, agricultural and environmental contexts within the Indus Basin.

Farmers in India and Bangladesh are 15 years ahead of their Pakistani counterparts. The governments in those countries support the farmers by allowing them to send energy back to the grid, which compensates them for their energy expenses in crop production, while the farmers there have also diversified their income sources by establishing poultry farms and other ventures in addition to farming.

There is an urgent need for proper guidelines to educate the farmers on efficient irrigation practices that considered both the quantity and quality of water. National guidelines for water accounting, water resource assessment, early drought warning systems and crop insurance systems were being developed.

A fundamental step is the establishment of a centralized, transparent water management authority to oversee distribution, conservation efforts, and infrastructure development. Efficient governance will ensure equitable access and sustainable utilization of resources. Additionally, modern irrigation techniques such as drip and sprinkler systems must be widely adopted to curb water wastage in agriculture, which remains the largest consumer of the country’s water supply.

Groundwater depletion is another critical concern. Recharging underground aquifers through regulated river flows and rainwater harvesting initiatives can help replenish diminishing reserves. Simultaneously, prioritizing less water-intensive crops and investing in research for drought-resistant agricultural practices will promote long-term sustainability.

Public awareness is equally crucial. Nationwide campaigns and school curricula should instill a culture of water conservation from an early age. Moreover, integrating advanced weather prediction technologies and resilient infrastructure can help mitigate the adverse effects of extreme climate events.

The gravity of Pakistan’s water crisis necessitates decisive action, backed by policy reforms, technological innovation, and societal engagement. Without immediate intervention, water scarcity will continue to threaten economic stability, food security, and the well-being of millions. The time to act is now.

A race against time

Pakistan has been facing a severe water crisis that is putting millions of lives at risk. Pakistan has already been placed in the critically water-insecure category, indicating that the country is facing a water emergency that requires immediate attention.

Pakistan is among the most water-stressed countries in the world, with rapidly declining per capita water availability, owing to an unbridled population and environmental factors. As the factors responsible for the shortage of water and its inefficient use are likely to get worse in the coming years, unless immediate action is initiated to ward off the apocalypse, poverty and food insecurity are forecast to surge.

Pakistan’s water crisis is no longer a distant threat. It is a present-day emergency requiring immediate action. With reservoirs running dry, groundwater levels depleting, and climate change worsening the situation, the country is at a crossroads. Policymakers must act decisively, moving beyond rhetoric and toward actionable solutions.

The quality of water available is also worsening. As the water table falls, soils are becoming saltier, making it difficult for farmers to grow crops. And as the population rises, wastewater and raw sewage end up in rivers due to a lack of treatment plants. Farmers downstream then use this water to irrigate their crops.

The challenge is formidable, but so is the opportunity. If Pakistan adopts a comprehensive, science-driven approach to water management, it can not only mitigate the current crisis but also build resilience against future threats. The alternative—a nation crippled by water scarcity, food insecurity, and internal conflict over dwindling resources—is too dire to contemplate.

The time for decisive action is now. Failure to confront this challenge will jeopardize the nation's environmental sustainability, economic resilience, and the well-being of future generations. Pakistan's survival hinges on its ability to secure its most precious resource – water. Climate change will make it much worse. The authorities must take steps for controlling population growth, carry out forestation and vegetation that helps percolation and in-filling of natural aquifer that serves as our water storage facility. Pakistan needs to have a development strategy that draws benefits from the direction in which the world economy is moving, so that we are not left behind while everyone else makes a successful transition to a low carbon economy.