Once gifted with plentiful water resources, Pakistan now finds itself teetering on the brink of a severe water crisis. Over the last few decades, there has been a sharp decline in the per capita water availability in country, which boasts of one of the best canals and river systems in the world. It has plummeted from approximately 5,300 cubic meters in 1947 to less than 1,000 cubic meters in recent years.

Water scarcity has put Pakistan in the category of critical water-scarce nations. Multiple factors such as water mismanagement, whopping population growth, climate change, inadequate infrastructure development, and inefficient water usage, besides others.

The multifaceted crisis of water scarcity is going to worsen in coming years if a comprehensive and integrated policy response, which transcends technical solutions and delves into the complex political economy of water, is not put in place. The factors, which have contributed to the current decline of water resources, are discussed in the following lines.

Inefficient water management practices have significantly contributed to Pakistan’s water woes. The country’s outdated irrigation methods, particularly flood irrigation, is one of the major factors leading to substantial water wastage. Agriculture consumes nearly 90% of Pakistan’s freshwater supply, yet the sector’s productivity remains low.

According to the Consortium for Development Policy Research (CDPR), Pakistan’s water productivity is among the lowest globally, producing only 0.13kg of agricultural output per cubic meter of water, compared to 1.3kg in the United States. Moreover, the underpricing of water has fostered a culture of irresponsible consumption to further exacerbating the crisis.

Climate change has intensified Pakistan’s water challenges. The country is among the top 10 most vulnerable to climate change, facing threats such as erratic monsoon patterns, receding glaciers, rising temperatures, and increased frequency of floods and droughts at the same time

Likewise, Pakistan’s population has surged from around 34 million in 1951 to over 225 million in 2024, intensifying pressure on water resources. This rapid growth has led to increased domestic, agricultural, and industrial water demands. Urbanization has further strained water supply systems, with cities like Islamabad, Rawalpindi, Karachi, and Lahore experiencing acute shortages.

The Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources (PCRWR) reports that per capita water availability has declined from 5,260 cubic meters per person in 1951 to 1,017 cubic meters in 2021, well below the internationally recommended threshold of 1,700 cubic meters per person per year.

Similarly, climate change has intensified Pakistan’s water challenges. The country is among the top 10 most vulnerable to climate change, facing threats such as erratic monsoon patterns, receding glaciers, rising temperatures, and increased frequency of floods and droughts at the same time.

The Indus River Basin, Pakistan’s primary water source, is highly sensitive to these changes. Glacial melt, which currently accounts for a significant portion of the Indus’s flow, is accelerating, leading to initial flooding followed by long-term water shortages.

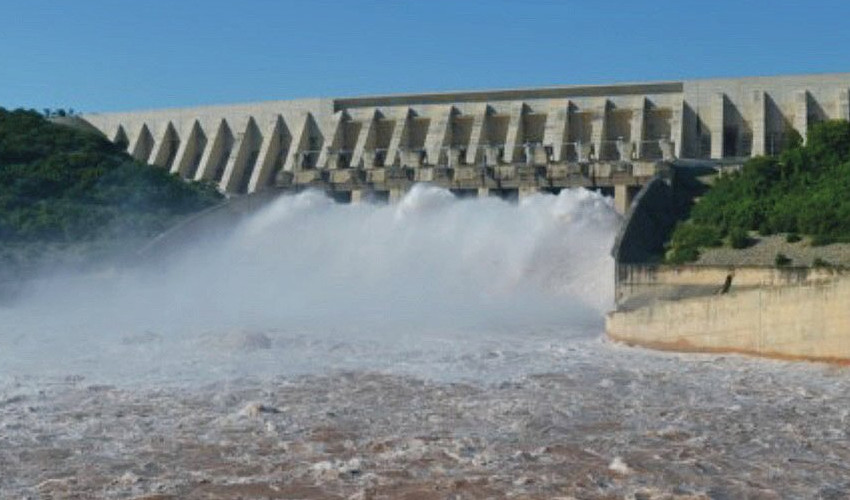

In the same vein, Pakistan’s water storage capacity is critically low, with reserves lasting only 30 days, compared to India’s 220-day supply. Political disputes have hindered the construction of new water reservoirs, while existing dams are nearing the end of their functional lifespan. Additionally, the country’s canal systems are inefficient, resulting in substantial water losses. Estimates suggest that Pakistan loses around 30 million acre-feet of water annually due to these inefficiencies.

The absence of effective water pricing and regulation has led to a pervasive culture of wasteful water use. Farmers often opt for water-intensive crops like sugarcane and rice, despite the country’s dwindling water reserves. Industrial activities, particularly in sectors like textiles and chemicals, contribute to groundwater depletion and contamination. Moreover, lack of public awareness and education on water conservation exacerbates the problem.

Above all, water scarcity has evolved into a complex political economy issue in Pakistan. Policymakers have traditionally viewed water management through a technical lens, focusing on supply-side solutions like dam construction. However, this approach overlooks the socio-political dynamics that influence water distribution and usage.

Inter-provincial disputes over water allocation, lack of consensus on infrastructure projects, and the influence of powerful agricultural lobbies have impeded comprehensive water reforms. Additionally, the underpricing of water reflects political reluctance to impose tariffs that could be unpopular among constituents.

Despite recognizing the severity of the water crisis, Pakistan has struggled to implement a cohesive strategy for water conservation and optimal usage. The National Water Policy of 2018 outlined key priorities but lacked effective implementation mechanisms.

Fragmented governance, weak institutional frameworks, and insufficient stakeholder engagement have hindered progress. Further, the absence of integrated water resource management has led to disjointed efforts that fail to address the root causes of the crisis.

However, water recycling remains an underutilized strategy. Investing in wastewater treatment and reuse can alleviate pressure on freshwater sources. Similarly, the alarming depletion of groundwater resources necessitates urgent attention. Unregulated extraction has led to declining water tables, particularly in urban centers. Implementing policies for sustainable groundwater management and promoting technologies for efficient water use are critical steps toward mitigating the crisis.

Addressing Pakistan’s water scarcity requires a well-knitted, integrated policy response that encompasses. Adopting modern irrigation techniques, enforcing water pricing that reflects scarcity, and promoting water-efficient crops is the need of the hour. At the same time, there is an urgent need to implementing policies to control population growth and manage urbanization to reduce pressure on water resources.

Policymakers also need to come up with strategies to mitigate climate impacts such as building resilient infrastructure and enhancing disaster preparedness. Climate change has drastically altered Pakistan’s hydrological cycle.

The 2023 UN Global Water Security Assessment underscores this risk, highlighting Pakistan among the 23 countries facing “critically insecure” water situations. The report warns that climate-induced shifts in water availability could lead to severe agricultural shocks, food insecurity, and internal displacement in Pakistan if urgent adaptation measures are not taken.

Pakistan needs to create a centralized water authority to harmonize water policies across provinces and sectors, ensuring transparency, accountability, and coordination. Prioritizing the construction of large and small dams, revamp irrigation systems, and support the adoption of water-saving technologies in agriculture and industry are also the need of the hour.

Pakistan needs to introduce water pricing to curb wastage, regulate groundwater extraction through licensing, and incentivize efficient practices as well as launching nationwide campaigns to educate citizens about water conservation, efficient usage, and the value of water. Development of the municipal wastewater treatment plants and encouraging industries to recycle water is another option to treated and reuse water in non-potable sectors.

Researchers should recommend incorporation of climate projections into long-term water planning and develop adaptive strategies to manage droughts and floods more effectively. Similarly, water data collection, analysis, and sharing is of vital importance to enable evidence-based policymaking and real-time water resource management.

Pakistan is running out of time. The 2023 UN Global Water Security Assessment has sounded the alarm — and rightly so. The water crisis is not only a looming environmental catastrophe but also a trigger for economic instability, social unrest, and public health emergencies.

If Pakistan is to avert a full-blown disaster, it must move beyond technocratic fixes and embrace an integrated approach that considers political economy, social equity, and environmental sustainability. Only through a unified, inclusive, and forward-looking strategy can Pakistan reclaim its future from the grips of water insecurity.